6 Sustainable and Healthy Fish to Eat (And 4 Types to Avoid)

Here's the scoop on the best sustainable and healthy fish to eat regularly according to experts and a few fish types they recommend you avoid.

16 Pumpkin Pie Recipes to Make for Thanksgiving

From traditional pumpkin pie recipes to elegant and creative variations (such as pumpkin pie pudding, cheesecake, and cupcakes), these scrumptious pumpkin pies will make your Thanksgiving holiday dessert a smashing success.

14 Easy Slow Cooker Appetizers that Make Entertaining Low Stress

These holiday slow cooker appetizers will hit the spot for every guest. Our recipes include sliders, dips, fondue, and more!

Godzilla Roll Sushi Bake

This sushi bake recipe makes your favorite sushi roll a breeze to make. Get the delicious taste with half the work by following our Godzilla Roll Sushi Bake recipe.

Indian Masala Chili

Indian Masala Chili

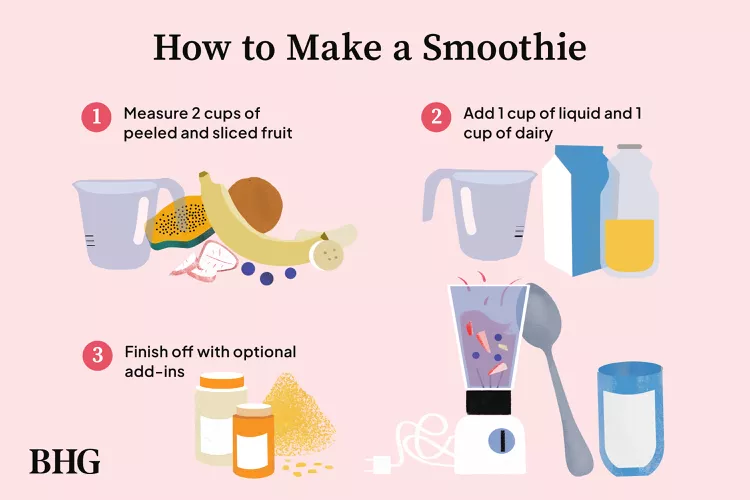

How to Make a Smoothie from Your Favorite Fresh Ingredients

Learn how to make a smoothie with your favorite fruits, veggies, and dairy or non-dairy products. Skip the pricey juice bar or bottled options.

Make-Ahead Mini Cheese Balls

Once you learn how to make cheese balls that you can customize—and then freeze for up to three months—you'll never host a party without them! Depending on which cheese ball seasoning you choose, this make-ahead cheese ball recipe can fit any season or color palette.

Eggplant "Meat" Balls with Chimichurri

Enjoy these plant-based meatballs for your next meatless dinner.

Slow Cooker Italian Sausage Grinders

Make hot Italian sausage subs for a crowd with this easy slow cooker sandwich recipe. This easy Italian sandwich recipe makes enough meat for 12 subs, so it's great for a party or potluck.

Low-Sugar Chocolate Chip Zucchini Muffins

Enjoy these moist healthy muffins for breakfast or with your afternoon tea.

How an Orchestra Orchestrates a Live Journey Through a Video Game

A controller will direct a conductor's baton during Journey's live performances at the Brooklyn Acad

Fashion and Beauty: 3 Hottest summer nail colours

This article discusses the latest nail color trends for the summer season. It highlights three popul

Marni SS25 Collection: A Story of Fashion and Beauty

The article explores how the "hero's journey" narrative structure is reflected in Marni's SS25 colle

Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show 2024 Makeup-Free Backstage Beauty With Tyra Banks & More Models

The 2024 Victoria's Secret Fashion Show is making a highly anticipated return to New York City, feat

5 Video Games Based On Hit TV Shows

The article discusses the cross-pollination between entertainment mediums, focusing on the trend of

“Classic part of the game”: GTA 6 Fans Worry as They’ve Not Seen 1 Iconic Part of the Grand Theft Auto Franchise Yet, While Others Hope It’s Cut

The article discusses the hype surrounding the highly anticipated Grand Theft Auto VI (GTA 6) and th

Spies, breakups and thick glasses: Philly’s Pig Iron obsesses over Aimee Mann in ‘Poor Judge

The article discusses a new theatrical production called "Poor Judge" by Pig Iron Theatre, which is

Weekend Entertainment Highlights: Lizzo, Diddy & More (November 30, 2024)

This text presents various news. Lizzo is on a weight loss journey and shows off her slimmer figure.

Skyline Chili voted ‘Best Regional Fast Food’ in US, according to new poll

Skyline Chili, a beloved Cincinnati-based fast food chain, has been named the "Best Regional Fast Fo

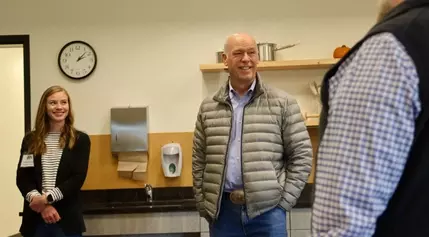

Governor Gianforte Launches 4th State Agency Food Drive on 5th Day of Giving

The Governor's Office announced the fourth annual state agency food drive competition on December 6,